Introduction

Peter Crowther (b. 1949) and James Lovegrove (b. 1965) are two British speculative-fiction authors who set out, according to the article on Escardy Gap by James Lovegrove on his website,

A short-story collaboration that ended up five hundred pages long, Escardy Gap was pure fun from start to finish. Pete and I set out to concoct an affectionate and respectful homage to Something Wicked This Way Comes, but, as the book evolved, we found we were creating something entirely different and altogether darker.

And how did they do?

Synopsis (*SPOILERS*)

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

The story begins with a framing segment of a New York City based author, apparently in the 1980's or 1990's, who is attempting to overcome his writers' block and write the great horror novel upon which he has been working for a long time. He's living a rather isolated life, with two friends in his building, and a cat in his apartment. He begins writing, and we read the novel.

The story is set in the small American town of Escardy Gap (pop. 792) sometime in the 1950's. The exact year is never mentioned, nor is the exact state, but it is somewhere in the deserts of the West. Escardy Gap is semi-isolated: it is built around the only spring for many miles around and hence is a fertile oasis in the midst of the desert. There is, however a railroad which enters the town through a tunnel, and a railroad station, where trains stop every few days. There is also at least one road out of town.

Escardy Gap is a good and wholesome town, populated by rather innocent and mostly-loveable people. It is in fact almost absurdly-idealized, and is clearly modelled on Ray Bradbury's rural America at its most nostalgiac.

To this town there comes unscheduled one Saturday a mysterious and sinister train, drawn by a black steam locomotive. The mere sound of its whistle is able to shatter nearby objects and, on the way into town, it briefly stops and its evil occupants somehow destroy the mind of an old man at an outlying farmhouse, who sees his dead wife as one of the passengers (from later happenings in the story, it becomes fairly obvious how this was done). Unfortunately for the townsfolk, they do not witness this initial event.

The train pulls into the station and its occupants emerge. They are a group of freakish people who call themselves "The Company," and pretend to be a traveling circus. The good people of Escardy Gap invite them to stay in their homes (which is odd even by 1950's small-town American standards, but may be a manifestation of the Company's powers), and the real show commences.

For the Company are in fact an alliance of evil demons, inhumans and mutants, all assembled by the power of The Angel (their train, which is actually a greater demon incarnate as a sort of cyborg vehicle) and led by the Angel's lieutenant, Jeremiah Rackstraw, who is either some sort of lesser demon or a once-human diabolist who decided to serve The Angel in return for power. Each has a unique power or powers, enough to make him (or her -- at least three are female) able to easily kill any normal unarmed human. And each is a serial killer, who delights in horribly murdering innocent victims. The fear, pain and death they cause somehow feed The Angel, making their relationship with their master a symbiosis.

Starting on Saturday night, the Company begin their murders. Their first killings are done surreptitiously with corpses either hidden or left in states where they no longer appear to be human remains (this is possible due to some of their specific powers), but on Sunday morning one of them leaves a murdered boy wrapped around the biggest and oldest tree in town.

The townsfolk come to the realization that there are murderers among them. Some fight, some hide, some try to flee, but they are for the most part overmatched. The phone lines have been cut and some who try to flee discover that there is a force field around the town which gruesomely kills anyone who attempts to pass. Two people -- the Mayor (an ex-Hollywood actor) and Joshua Knight (a 12-year-old genius) eventually realize that the forcefield only extends to but not under the ground, and thus offers a passage to safety.

This is when the story gets really weird.

Somehow, when the Mayor and Josh escape through the tunnel, they find themselves in the New York City of the writer, coming out of a culvert in Central Park right under the writer's nose. The writer can apparently create worlds out of his imagination and materialize the inhabitants of these worlds in the "real" world, and the two friends (and the cat) he thought he had were really just more products of his imagination.

But because the Mayor and Josh were only meant to exist in the imaginary world of Escardy Gap, they begin to (painfully and disgustingly) dissolve soon after the writer gets them safely to his apartment. The writer knows only one way to save them -- to write them back into Escardy Gap and somehow give the story a semi-happy ending. So he again starts writing ...

The Mayor and Josh return to Escardy Gap. They decide that they have to stop The Company and save whoever else of the townsfolk have managed to survive so far.

They realize -- due to the nature of a trap which Josh had previously escaped -- that The Company's train is a living being and probably the source of their power. They decide that to defeat The Company, they must somehow slay this entity.

The Mayor gives his life to distract The Angel's guardians while Josh sneaks under the train. There, he finds a hatch leading to the (literal) guts of the locomotive. Josh tears apart The Angel's internal organs, killing (or banishing) the greater demon. Upon The Angel's death, Jeremiah Rackstraw ages, turns to a skeleton and disintegrates (making it obvious that Rackstraw's life force was tied to that of The Angel). The other monsters also either die -- or flee, the story doesn't make it obvious which. Josh walks through the ruined and burning town, of whose folk he is one of the few survivors -- and mourns the death of Escardy Gap.

The writer remembers that there was at least one other character -- a beautiful, intelligent and lonely woman, who was a science fiction and fantasy writer -- who also survived the destruction of the town, though he had forgotten to write what happened to her.

Realizing that she is his ideal woman, he returns to the Central Park portal leading to Escardy Gap and vanishes..

Here the story ends.

The Good

The Angel and its Company are a good enabling concept, providing a logical reason for a large group of disparate monsters to attack a single small town. The Angel itself, and each individual described member of The Company, are interesting monsters, with imaginatively chosen powers and limitations. Each of them might, in itself, be the subject of a good short story or novel.

Crowther and Lovegrove remembered that we must first care about a place to care about its destruction. They make the reader care about Escardy Gap and its inhabitants, so that we care about their destruction, and properly hate The Company for their foul deeds. This makes the story more horrifying and the eventual defeat of the villains more satisfying.

The Bad

Monsters Without a Cause

The monsters need origin stories and motivations beyond "we're evil and we like killing people." To begin with, there are strong implications in the story that not all of The Company began as demons: Rackstraw seems to have begun as some sort of human diabolist or sorceror; Agnes Destiny may be a mutant; and the Changeling is a member of a nonhuman race which secretly evolved (or otherwise appeared) on Earth but the members of which have mostly forgotten their own true natures and powers (it appears to be some sort of small shoggoth, similar in some ways to Michael Shea's "Fat Face").

While it's obvious that only the most evil of people or creatures would be selected by The Angel and Rackstraw to join The Company, and any remaining tendencies toward good would be rather rapidly destroyed by their line of work, there is nothing about being a mutant or a nonhuman which would automatically make one an evil murderous sadist. There need to be explanations at least hinted at for why the main antagonists are the way that they are, and Crowther and Lovegrove provide none.

Too Nice For Their Own Good

The inhabitants of Escardy Gap are naive and (prove themselves to be) helpless beyond belief, and their utter lack of effective resistance undermines some of the sympathy which the reader might otherwise feel for them. Specifically, it is foolish for them to take a group of weird outsiders into their own homes, especially when alternatives exist (the town actually has a small hotel). This is overly-trusting to the point that it makes me wonder if this was some psychic influence exerted by The Angel.

It is believable that the murders of Saturday night go undetected. One might distrust strangers but one would not logically assume them to be a band of psychopathic brigands; furthermore some of the specific methods of murder are ones possible only for metahumans (for instance, one couple is slain by a man who tricks them into smoking an incredibly-addictive enchanted tobacco which dissolves them down to blobs and them piles of ash).

What is not believable, save by means of mind control, is the way in which the townsfolk act after the discovery of the corpse of Tom Finkelbaum on Sunday morning. Specifically, no one responds to this as a major crime demanding any sort of police investigation, and it seems to occur to none or very few of them that the obvious suspect in the murder of Tom Finkelbaum would be one of The Company, since the correlation between The Company's arrival and the murder would otherwise have to be an incredible coincidence..

I can believe that a town of only 792 people might lack a full-time police department, but in that case (1) there would be someone in or near the town who acted as de facto or part-time constable and (2) standard procedure in the event of a serious crime (such as murder) would be for the town authorities to contact some higher law enforcement agency -- the County Sheriff's office (Escardy Gap does not appear to be a county seat), State Police or even Federal Bureau of Investigation. And yes, Escardy Gap would in reality have some sort of law enforcement system, some sort of way to report crimes and arrest criminals. Nice and peaceful a town as it is, there must sometimes be fights, robberies, and other minor offenses.

Now, I'm not saying that a law enforcement response would have worked. The Company would not have submitted to being rounded up and questioned, and the moment that any attempt was made to call for outside help, the cut phone lines and force field would have been discovered.

What I am saying is that the discovery of Finkelbaum's corpse should logically have precipitated the climax. The town authorities should have confronted Rackstraw, and The Company then manifested their full power in defiance of Escardy Gap. At this point, the masks would have gone down, and the large-scale death and destruction begun.

No, instead the townspeople just scream in panic and then mostly try to ignore what just happened. The climax actually comes when many of the townsfolk go to the movies that Sunday afternoon, attending them with The Company among them. There is some implicit mind control here, for instance The Company is able to get in without paying (why they care to do this isn't clear, as they could obviously just pick up the till on the way out and thus get back their money, assuming that cash money really matters all that much to supernatural metahuman brigands who sack whole towns).

This ends in the predictable manner, when The Company simply slaughters everyone else in the movie theatre. After that, there is still no grand moment of realization: instead, The Company simply disperses and begins finishing off everyone else in the town one at a time.

The Mayor fails his town completely. It is not until hours after the Finkelbaum murder that he realizes that the phone lines have been cut, and he makes no real effort to recuit any assistance. The Mayor winds up with Josh and (for a while) Doc Wheeler as an unofficial resistance group more or less by accident. Each individual inhabitant of Escardy Gap is left to flee, fight and (mostly) die alone, or with no aid save that of his own family.

The ineffectiveness of this response implicitly comes from two factors, which I think derive from the limitations of either Crowther and Lovegrove's, or The Writer's, knowledge of real 1950's America.

Tougher Than They Looked

You may remember that the adult characters in 1950's TV and movie rural America were really nice folks. Sweet. Kind. Even innocent.

This is horsefeathers.

In fact, the adults of the 1950's had been through Hell, and to the extent that they really did act that nice, did so because they had seen enough nastiness already to suit them for the rest of their lives, thank you. These were people who had already survived some rather seriously-dangerous events.

Take "adults" c. 1955 as being around 25-65 years old, which means that they were born around 1890 through 1930. If you were born around 1890, you lived through, in succession:

1. The Panic of 1893, a recession roughly as bad as the one we're in right now, which lasted five years and saw unemployment rates reaching as high as 12-18 percent (at a time when there was no unemployment insurance!!!), and which probably caused hundreds of thousands of excess deaths in America;

2. World War One, which should require no introduction but which we should note included the killer flu pandemic of 1918 (inspiration for Lovecraft's "The Last Test" and hence indirectly for King's The Stand), which between them shattered Old Europe and caused hundreds of thousands of deaths in America;

3. The Great Depression, which lasted over a decade and saw unemployment rates as high as 25 percent (resultiing in hundreds of thousands and possibly millions of excess deaths due to malnutrition, exposure and related causes), followed almost immediately by

4. World War Two, in which America came close to defeat at points, and in which America lost almost half a million dead and suffered millions of severely wounded, ended by our invention of the atomic bomb which introduced a new deadly peril into the world, and recently

5. The Korean War, which claimed over 33 thousand American lives with over a hundred thousand severely wounded.

Someone who survived any or all of these events (and even someone born in 1930 would have lived through the last three of them) may have been nice (because they were very, very happy that they were now living in pece and prosperity), but they also tended to be rather tough, and were not entirely unaware of the existence of evil in the world -- to put it mildly.

To Arms?

The three wars on that list remind us of something else, which is that the early to mid 20th century was not exactly what one would call a time of overall peace. Americans, particularly rural Americans, would in any case have owned and become fairly good shots with a variety of firearms ranging from pistols up to bolt-action rifles. The warlike nature of the era meant that a significant minority of Americans, even in small towns, were also veterans, and furthermore that it was considered not merely acceptable but even patriotic to own and practice with firearmes.

The reasons why this is important is that it is actually mentioned in the novel that many if not all of the members of The Company are vulnerable to firearms. Yet The Company seems not to take the threat of guns into account, until one of their victims, driven crazy by the sight of the forcefield, shows up at The Angel with a gun in hand. And then he fails to make any effective use of his weapon.

Nor does it occur to the Mayor, Josh or the Doc -- or any sane character in the story -- that it might be wise to bring out some firearms. They are, of course, unaware that The Company is vulnerable to guns, but then they have no particular reason to believe that they aren't vulnerable to guns either. The only reason for them to believe this would be that movie monsters are often immune to guns -- though this wasn't usually the case in the movies of the 1950's!!!

Even though the townsfolk, at the point of their final slaughter, are mostly aware of the fact that their town is under attack by ruthless and atrocious murderers, and are mostly at home trying to protect their families, nobody seems to be using guns. During the final wave of murders, we don't even hear any gunshots. This is incomprehensibly passive behavior, from an American point of view, and I daresay that even most British towns would by this point have broken out their (smaller) arsenals and decided to sell their lives dearly.

For that matter, even though the Mayor and Josh eventually realize that they have to destroy a steam locomotive, which they have no reason to assume is vulnerable to their unaided human strength, it never occurs to them to get any explosives (dynamite would be available in the general store of any mid-20th-century small American town). It's possible that the Mayor's death would have been unnecessary had they done that, as we have no reason to assume that The Angel was armored beyond the norm for an ordinary steam locomotive.

Paging Miss Norton ...

There is one character in the book who is both interesting, srongly-drawn and totally wasted. That is Sara Sienkiewicz, who is an intelligent, imaginative, strong-minded writer of science fiction and fantasy, who one would expect to swiftly grasp the situation (she's been published in and presumably reads Weird Tales) and propose effective action from the first appearance of The Company. When I saw that she was in the story, I expected her to play a major role in fighting the monsters.

Nope. Rackstraw considered her an especially delectable treat (she has a truly good soul of exceptional purity) and had one of his minions put her into an enchanted slumber for his own later enjoyment (at the end of which he intends to kill her) This never comes to pass, since she wakes up toward the end and wanders dazedly out of town to collapse in a house which The Company have already plundered. Thus, she is overlooked by the monsters, then The Angel is destroyed, and hence Sara is one of the few known survivors of the townsfolk, availabe to become the object of The Writer's final quest.

Which is to say ...

The whole freaking purpose of this character was to give The Writer a love interest which would tempt him to enter his fictional world at the end of the story!!!

Now, I am very far from being a radical feminist. The fact that a female character in a story may exist mostly to be endangered by the villain does not bother me as deeply as it does those who have had the misfortune to have been brainwashed by Political Correctness.

However ...

... when a writer introduces an admirable, loveable and obviously-competent character into a story (Seinkiewicz is selling to paying markets including the Saturday Evening Post at a time when there still existed considerable prejudice against female sf/fantasy writers, and come to think of it against science fiction and fantasy themselves) and then just tosses the character aside for the whole story, giving the character absolutely no chance to show any of her skills or use them effectively in the resolution of the plot, and especially when this character is rather obviously based on a writer for whom I have the most profound admiration, and who was famous for stories including strong female characters who were not merely Distressed Damsels (in an era where such damsels were close to the norm) ... well, I cry "foul."

Muggers, Muggers Everywhere

There is a throwaway scene where The Writer, the Mayor and Josh just happen to encounter three punks on the streets of New York, whom The Writer manages to appease by giving $50 and who seem unaccountably unafraid of the three punks, which seems to be in there to demonstrate

(1) - How much more dangerous the streets of a 1990's big city are than Escardy Gap and

(2) - How in the 1950's nobody was scared of teenagers while by the 1990's everybody needs to be.

The writers get everything about this wrong.

To begin with, the streets of New York City are not more dangerous than Escardy Gap, because Escardy Gap has been overrun by demons. Both the Mayor and Josh have met and been threatened by Rackstraw and others of The Company personally, and having some experience of New York City steet punks, I will categorically state for the benefit of anyone who doubts this that they are not scarier than murderous metahuman monsters!

Secondly, it is fairly improbable that three random punks, who in the story shown no sign of being armed with as much as knives, would attempt to mug a group including two male adults and one male child. This is especially the case if the environment was in public and by daylight. And no, Central Park is not overrun with criminals to the point that no one would take notice of such a crime.

Thirdly, about the worst thing that one can do when confronted by potential muggers is offer them money to go away. Doing so implies that one has more money and that one is frightened enough that one might be induced to yield these additional funds. The writers seem to have no clue about the motivations of petty crimianls.

Finally, not only were people in the 1950's not unafraid of teenagers, but in fact this was the period in which the concept of "juvenile crime" as a special and growing problem became of general concern. Watch any of the movies from this era. (One could if one were inclined push this back a little to the late 1940's). Admittedly, it probably isn't normally a problem in Escardy Gap itself.

The Strange

The whole plot where it turns out that not only is Escardy Gap a tertiary world comes across as something of a deus ex machina. There is no real foreshadowing that The Writer has the ability to bring his imaginary creations to physical reality.

There is no obvious reason given why The Writer is alone or why he is so insanely cynical about the world (though his attitude might be an explanation for his loneliness). He comes across as a manic-depressive, and when one adds to this that he is unaware that his best friends were created from his own imagination, a psychotically-deluded manic-depressive at that.

I'm also kind of curious how The Writer would handle the inevitable explanation to Sara of his origin.

"Yes, I'm the person who created your whole fictional world, which is identical to my 1950's but has this town called Escardy Gap."

"Wait, you mean you created me, my town, and all the people in it?"

"Yep."

"Which got destroyed and its people horribly slaughtered by monsters?"

"Um ... yeah."

"And was the appearance of these monsters a coincidence?"

"Well, no ... um ... I was writing a horror story, you see ... so, do you love me?"

For that matter, what happens to The Writer when he enters Escardy Gap? Is he, as the world's Creator, super-powerful there? As a non-native, does he have to worry about eventual disintegration like his characters in our world? Or is he just a normal human being there?

Are any of the monsters still in Escardy Gap? If so, isn't he worried about encountering them? Even if there are no monsters in Escardy Gap, what happens when the people of that world notice the town's annihilation (it's hardly subtle, Rackstraw set the place on fire) and The Writer is found to be the only stranger alive in town, with absolutely no record of his existence anywhere in that world).

Then again, he brought his typewriter, which seems to be a sort of Word Processor of the Gods, so maybe he can just write himself whatever background suits his needs. Maybe he can even write Sara as being deeply in love with him from first sight.

Frankly, given how insane The Writer appears (to me) to be, I'm glad I don't live in that secondary world. And only in part because of the obvious monsters.

Conclusion

Escardy Gap is an enjoyable (I had fun reading it) but logically-flawed horror-fantasy, which left a lot of loose ends. The motivation of the monsters is pretty much taken for granted, and the townsfolk seem to have a whole bucket full of Idiot Balls (perhaps on loan from the school gym) which they spend most of the story passing around. The Writer's version of the 1950's is poorly-researched and inconsistent (which may or may not be intentional on the part of the actual writers) which directly drives (or fails to drive) key parts of the plot.

Worth reading, but can't take it very seriously.

The journal of old and new science fiction, fantasy and horror stories, poems, essays and reviews.

Saturday, July 28, 2012

Wednesday, July 25, 2012

Retro Review - "Or All the Seas with Oysters" (1958) by Avram Davidson

"Retro Review -

'Or All the Seas with Oysters' (1958)

by Avram Davidson"

by Avram Davidson"

(c) 2012

by

Jordan S. Bassior

Introduction: I first encountered this Hugo-winning story by Avram Davidson (1923-1993) as a teenager, and failed to appreciate it. Re-reading it recently, I was struck by its economy and power.

*** SPOILERS (in case someone hasn't already read this tale) ***

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Synopsis: Oscar and Ferd are partners in a bicycle shop, but they have drifted apart as friends. Oscar is an big, beefy, practical sort of guy into

beer, bowling and women. Any women. Any time.

while Ferd is an intellectual fellow who likes

books, long-playing records and high-level conversation.

Ferd becomes obsessed with the idea that safety pins seem to keep disappearing while there are always too many coat hangers. One day, in a fit of frustration at Oscar's easy ways with women and the misuse of a red French racing bicycle which Ferd was fixing up, Oscar tears up the seats and tires and smashes the spokes of the bike.

Two weeks later, the bicycle is intact, and Oscar is amazed at how well Ferd fixed it up. Except that Ferd never fixed it up. It is at this point that Ferd comes to his Big Realization:

"... suppose there are ... things ... that live in people places. Cities. Houses. These things could imitate -- well, other kinds of things you find in people places ...

"Maybe they're a different kind of life-form. Maybe they get their nourishment out of the elements in the air. You know what safety pins are -- these other kinds of them?... the safety pins are the pupa-forms and then they ... hatch. Into the larval-forms. Which look just like coat hangers. They feel like them, even, but they're not ...

"All those bicycles the cops find, and they hold them waiting for owners to show up, and then we buy them at the sale because no owners show up because there aren't any, and the same with the ones the kids are always trying to sell us, and they say they just found them, and they really did because they were never made in a factory. They grow. You smash them and throw them away, they regenerate ..."

Ferd goes on to postulate a whole ecology of "false friends" ... creatues that mimic human things.

Oscar scoffs at Ferd's idea. He insists that Ferd conquer his delusion by trying to ride the red French racer. But when Ferd does, the bike throws him, somehow scratching his cheek.

Oscar is telling this story to Mr. Whatney, who has come into the store. Ferd talks about the new special bicycles he has:

"... Combines the features of the French racer and the American standard, but it's made right here, and it comes in three models -- Junior, Intermediate and Regular. Beautiful, ain't it?"

Mr. Whatney asks

"By the way ... what's become of the French racer, the red one, used to be here?"

Oscar's face twitched. Then it grew bland and innnocent and he leaned over and nudged his customer. "Oh, that one. Old Frenchy? Why, I put him out to stud!"

And they laughed and they laughed, and after they told a few more stories they concluded the sale, and they had a few beers and they laughed some more. And then they said what a shame it was about poor Ferd, poor old Ferd, who had been found in his own closet with an unravled coat hanger coiled tightly around his neck.

Analysis: This is intellectual rather than gruesome horror, for all that it ends in violent death. The main terror lies in the idea that unknown life forms mjight be among us, hiding in plain sight by mimicking everyday things, and might be willing to kill to protect themselves and their secret.

It is also very clearly science fiction horror. I missed this point as a young man, when my definition of "science fiction" was far too narrow. Really, though: is there anything in this tale which is scientifically impossible? Yes, our kind of life couldn't do what these mimics do, but as poor damned Ferd points out

"...Maybe they're a diffefrent kind of life form ..."

Maybe they are.

There is also a subtle character-generated horror here. The story strongly implies that Oscar knows about the "false friends" -- that he knew at least after Ferd's revelation and death, and might have known even before Ferd realized what was going on. Certainly, he's taking advantage of it after the fact -- he really has put Old Frenchy out to stud, and has obviously gotten the hybrid bicycles from Frenchy and one or more American standards.

The vein of this horror runs deep. Not only is it a personal betrayal -- and how did Ferd wind up in the closet with the coat-hangers? -- but it is the betrayal of the intellectual, who reasons out a relationship, by the man of the world, who simply takes advantage of it without thinking too hard about its implications. Ferd was horrified by the false friends; Oscar simply uses them to breed more bicycles.

In a sense, Oscar was the falsest friend of all.

Addendum: Similar premises were used in Donald Wollheim's "Mimic" (1950) and Lisa Tuttle's "Where the Stones Grow" (1980). Wollheim's work, later made into a movie by Guillermo del Toro (1997), is about giant insects which have evolved to mimic human beings. Lisa Tuttle's tale is about silicon-based life which secretly shares the planet with Man, and keeps its secret by slaying any humans who witness them move. The notion of secret life passing among us undetected is inherently terrifying: for it means that the monsters are already here, it's too late to close the door.

Sunday, July 22, 2012

Retro Review - "We Purchased People" (1974) by Frederik Pohl (*MAJOR SPOILERS*)

"Retro Review of

'We Purchased People' (1974)

by Frederik Pohl,"

(c) 2012

by Jordan S. Bassior

Introduction:

Frederik Pohl (b. 1919) is a grand master of science fiction, most famous for his novel (co-written with C. M. Kornbluth) The Space Merchants (1952), which was one of the first American science fictional examples of a corporate-dominated future society; and his "Gateway" stories about humans exploring the relic interstellar travel system left by the vanshed Heechee. This is a short but powerful story about a man who has been enslaved to aliens.

Synopsis:

Not so far in the future -- perhaps some time in the early 21st century -- several races of interstellar aliens have made contact with Earth by tachyonic radio, and rather than send starships or build android agents, have instead adapted a naturally-occurring resource to their ends: human beings. And most of the human race doesn't mind this, for the aliens have a lot of knowledge to offer in trade.

... the star people had established fast radio contact with the people of Earth, and ... in order to conduct their business on Earth, they had purchased the bodies of certain convicted criminals, installing in them tachyon fast-radio tranceivers.

The aliens control and communicate with these "purchased people" through the FTL links, and use them to carry out various tasks: mostly, diplomacy and the purchase of objects interesting to the aliens for their own not-always-comprehensible reasons.

Art objects they admired and purchased. Certain rare kinds of plants and flowers they purchased and had frozen at liquid-helium temperatures. Certain kinds of utilitarian objects they purchased. Every few months, another rocket roared up ... and another cargo headed for the Groombridge star, on its twelve-thousand-year voyage ...

Or longer, or shorter, depending on the particular group of aliens. As for the economics:

Each rocket cost at least $10 million. The going rate for a healthy male paranoid capable of three or more decades of useful work was in the hundreds of thousands of dollars, and they bought they by the dozen.

Wayne Golden, a serial killer who murdered several young women out of obscure and foul impulses

I never molested any of them sexually, you know. I mean in some ways I'm still kind of a virgin. That wasn't what I wanted, I just wanted to see them die. When they asked me at the pre-trial hearing if I knew the difference between right and wrong I didn't know how to answer them. I knew what I did was wrong for them. But it wasn't wrong for me; it was what I wanted.

is one such purchased person. As with all of these slaves, they've installed his tachylink behind an oval gold plate in his head. Everyone who sees him knows what he is, despises him for his status and for the crimes he must have committed to be sold to the aliens, and knows his economic importance.

Most of the time, Wayne runs errands for the Groombridge aliens. The aliens can control him through his implant, either directly or by sending him pain when he does something they don't like, or fails to do something they desire. They can read his thoughts, and they send him pain if he thinks something they sufficiently dislike: mostly regarding his past murderous actions. Self-maintenance (eating, sleeping, hygiene) must be performed in moments of time snatched between these errands.

Every now and then, at unpredictable intervals, they give him some time off. During these periods, he can do what he wants, as long as it's neither self- or other-destructive. Wayne greatly values these times, as one might imagine.

Improbably, Wayne has fallen in love with another purchased person, Carolyn, whom he has met on assignement. She is owned by the same group of aliens, which means that they can hope for some vacation at the same time, but so far they have never been able to do more than snatch minutes here and there for conversation.

Then, Wayne is given an indefinite leave, and he is able to meet Carolyn. They go to a hotel. She tells him that this has been arranged by the Groombridge aliens, who would be interested in observing them having sex through the link. This repulses Wayne, but then (as he perceives) the aliens take him over through the link and

************SPOILER SPACE*************

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

make him kill Carolyn.

Or at least he thinks that the aliens made him do it.

But then, switching to the alien POV, we learn that actually

It was discovered that when control was withdrawn he became destructive, both to others and to himself. The conjecture has been advanced that that sexual behavior which had been established as his norm -- the desruction of the sexual partner -- may not have been appropriate in the conditions obtaining at the time of the experimental procedures. Fufther experiments will be made with differing procedures and other sexual partners in the near future. Meanwhile Wayne Golden continues to function at normal efficiency, provided control is not withdrawn at any time, and apparently will do so indefinitely.

Analysis:

It's not that the alien control made Wayne kill Carolyn. It's that the alien control was what was preventing Wayne from killing Carolyn (and possibly other people) as he did before: when it was withdrawn for a sufficiently long period of time, and he was presented with a sexual opportunity, Wayne reverted to his normal state of being a sexually-motivated serial killer.

Wayne, of course, didn't see it that way. He blamed it on the aliens: not in the sense in which it really was their fault (they'd set up the encounter as an experiment) but in the delusion that they had taken him over when he murdered Carolyn. In fact it was Wayne's own sick and evil nature which was directly responsible for the killing: he could not handle the reality of sexual attraction to a woman.

In a way this is analogous to the Earth's selling of slaves to the aliens. It is true that the aliens offer knowlege for large amounts of financial credit, and offer the credit thus gained for their living drones. But the transaction is voluntary on our part: it is our desire for easy knowledge, and the lack of value we place on the lives of the severely and violently insane, which provides people for purchase.

There is of course an obvious analogy here with the West African slave trade. The Europeans came bearing items relatively cheap for Europe to manufacture, because of Europe's slightly more advanced technology (cloths from mechanically-better looms, liquors from more advanced chemical processes, and so on) and were able to exchange these to native potentates (usually through Arab middlemen, though this is digression) in return for human beings who for whatever reason the native rulers no longer valued (they were often previous slaves, prisoners of war, or criminals). Without this cooperation from the natives, the slave trade would have been difficult, or perhaps impossible.

The story is chilling on multiple levels. On the most obvious level, it is horrifying because it is being told mostly form the POV of one of the "purchased people," and we get to see just how unpleasant it can be. For instance, at one point, he is forced to soil himself in front of a whole international conference because the aliens forget he needs to go to the bathroom -- this incident is in some ways more painful to read than the ones where the aliens outright make him do things, because while few of us have been mind-controlled by aliens, all of us have at one point or another at least come close to losing excretory control in public.

On the next level, it is horrifying because Wayne Golden is a rather disgusting person. He's no undeserving victim, he really did kill a bunch of innocent young women for the sake of gratifying his own depraved sexual impulses, and one of the questions raised by this story is "Does he deserve this?"

His fate is indeed horrible (enslaved to aliens until the day he dies, and dies probably because they've decided he's now useless to them), but then his deeds were also horrible. Human justice, in the absence of aliens, would have gotten him either death, life imprisonment or (his actual previous state) probable lifelong incarceration in an insane asylum. It is arguable which fates are worse: the ones he meted out to his victims, the one he was previously suffering in the mental hospital, or the one to which he has been sold.

It is horrible that he should fall in love only to murder the object of his adoration. It's obvious that what Wayne was feeling was some sort of love: how true was the love is open to debate. There was some obvious self-deception here: Wayne's perversion obviously comes in part from a combination of sexual desire and an inability to accept the reality of female sexuality, as witness his excuse to himself for murdering an eleven-year-old girl, nine years ago:

... if I hadn't done her she would have been twenty or so. Screwing all the boys. Probably on dope. Maybe knocked up or married. Looked at in a certain way, I saved her a lot of sordid, miserable stuff, menstruating, letting the boys' hands and mouths on her, all that ...

(at which point the aliens send him pain to stop this line of thought).

Note Wayne's assumptions and logic, or lack of logic. That being "twenty" means being promiscious or addicted to drugs. That pregnancy and marriage are worse than being violently murdered. That killing someone is "saving" them ... from life? Keep in mind that Wayne neither knew his victim nor had any real reason to assume that any of the bad things on his list would have happened (well, aside from menstruation), and most humans would probably consider the combination of sex, preganancy and marriage to be an overwhelmingly good life path, if not combined with the promiscuity and drug abuse.

Pohl here has the mentality of a certain type of serial killer dead accurate: the killer rejects life in general, and murders from nihilism, constructing rationalizations to avoid hating himself. Wayne in point of fact is not someone one would want to have freely wandering the world: the combination of his impulses and his rationalization makes it highly likely that he will kill again and again if not kept under control, whether in the crude physical sense of incarceration or the more advanced mental sense of the alien mindlink.

Which puts one in the interesting position of defending slavery. For the aliens' offer makes sense: it's good for the vast majority of people on the Earth, and the few people for whom it is really, really bad (the slaves) are people who in any case would be sentenced to death or life imprisonment, either of which is arguably worse than slavery to the aliens.

On the other hand, do we really know that all the Purchased People are at least as bad as Wayne? And slavery to the aliens does mean death in the end -- from overstrain and eventual disposal in "three decades" or more, or as an experimental subject as happened to Carolyn. We incidentally have no idea what Carolyn did to be sold into slavery -- it might have been something for which the normal penalty would have been far short of life imprisonment or death.

And what about the wrongfully-convicted? There is, as far as we know, no appeal from being Purchased, though it's possible that the aliens might in some cases allow resales. Certainly the Purchased Person himself would lack the time to start any sort of appeal, even if the aliens did not stop him from doing so on his free time. It seems to me that an innocent Purchased Person would be as unlikely to ever be released to return home as would a black slave already in the New World.

This gets into the final chill I get from the story.

People Purchase -- especially of the worst criminals -- makes sense. Not only in the context of the storyverse, but in general. Assuming the technological ability to implant mind control units, and some distance or other reason why you wouldn't want to use your own valued people to do the job, it's economically and even socially reasonable to use society's rejects as living drones. It's socially easier the less they are wanted: obviously it would be much more acceptable to use someone like Charles Manson for this purpose than it would be to use Harry Hooch the alcoholic who lives under a bridge.

And it is a plausible alien contact scenario. Aliens might find it difficult to physically cross interstellar distances, or to live under our environmental conditions. Living remotes -- essentially bioroid drones -- would be an obvious alternative, especially if they had FTL radio (which might be easier under real-life physics to develop than would be macroscopic FTL travel). If they have enough of an understanding of living neural nets, using the existing bioroids -- us -- might make more sense than either transporting them across interstellar distances, or assembling them on site on Earth.

Indeed, if the story were being done today, one obvious variant would be to use some sort of mind-control meme --- essentially a "computer virus" transmissible to our brains --- compelling the slave to check in at intervals through a single shared FTL radio -- rather than the FTL radio implants, which might be difficult to put in the limited space of a human cranium. This is if anything a creepier idea, since it would then be much less obvious at a glance who was a Purchased Person, and what if the meme was inter-human transmissible and the aliens decided to do a little freelance slaving ...?

Conclusion: In short, a deeply chilling and yet mostly hard-SF horror story, which I recommend to one and all.

Saturday, July 21, 2012

Reprint - "The Jameson Satellite" (1931) by Neil R. Jones

THE JAMESON SATELLITE

By NEIL R. JONES

The mammoths of the ancient world have been wonderfully preserved in the ice of Siberia. The cold, only a few miles out in space, will be far more intense than in the polar regions and its power of preserving the dead body would most probably be correspondingly increased. When the hero-scientist of this story knew he must die, he conceived a brilliant idea for the preservation of his body, the result of which even exceeded his expectations. What, how, and why are cleverly told here.

PROLOGUE

The Rocket Satellite

In the depths of space, some twenty thousand miles from the earth, the body of Professor Jameson within its rocket container cruised upon an endless journey, circling the gigantic sphere. The rocket was a satellite of the huge, revolving world around which it held to its orbit. In the year 1958, Professor Jameson had sought for a plan whereby he might preserve his body indefinitely after his death. He had worked long and hard upon the subject.

Since the time of the Pharaohs, the human race had looked for a means by which the dead might be preserved against the ravages of time. Great had been the art of the Egyptians in the embalming of their deceased, a practice which was later lost to humanity of the ensuing mechanical age, never to be rediscovered. But even the embalming of the Egyptians—so Professor Jameson had argued—would be futile in the face of millions of years, the dissolution of the corpses being just as eventual as immediate cremation following death.

The professor had looked for a means by which the body could be preserved perfectly forever. But eventually he had come to the conclusion that nothing on earth is unchangeable beyond a certain limit of time. Just as long as he sought an earthly means of preservation, he was doomed to disappointment. All earthly elements are composed of atoms which are forever breaking down and building up, but never destroying themselves. A match may be burned, but the atoms are still unchanged, having resolved themselves into smoke, carbon dioxide, ashes, and certain basic elements. It was clear to the professor that he could never accomplish his purpose if he were to employ one system of atomic structure, such as embalming fluid or other concoction, to preserve another system of atomic structure, such as the human body, when all atomic structure is subject to universal change, no matter how slow.

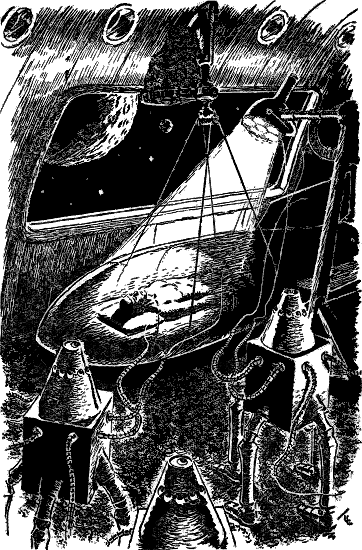

It glowed in a haze of light, the interior clearly revealed.

He had then soliloquized upon the possibility of preserving the human body in its state of death until the end of all earthly time—to that day when the earth would return to the sun from which it had sprung. Quite suddenly one day he had conceived the answer to the puzzling problem which obsessed his mind, leaving him awed with its wild, uncanny potentialities.

He would have his body shot into space enclosed in a rocket to become a satellite of the earth as long as the earth continued to exist. He reasoned logically. Any material substance, whether of organic or inorganic origin, cast into the depths of space would exist indefinitely. He had visualized his dead body enclosed in a rocket flying off into the illimitable maw of space. He would remain in perfect preservation, while on earth millions of generations of mankind would live and die, their bodies to molder into the dust of the forgotten past. He would exist in this unchanged manner until that day when mankind, beneath a cooling sun, should fade out forever in the chill, thin atmosphere of a dying world. And still his body would remain intact and as perfect in its rocket container as on that day of the far-gone past when it had left the earth to be hurled out on its career. What a magnificent idea!

At first he had been assailed with doubts. Suppose his funeral rocket landed upon some other planet or, drawn by the pull of the great sun, were thrown into the flaming folds of the incandescent sphere? Then the rocket might continue on out of the solar system, plunging through the endless seas of space for millions of years, to finally enter the solar system of some far-off star, as meteors often enter ours. Suppose his rocket crashed upon a planet, or the star itself, or became a captive satellite of some celestial body?

It had been at this juncture that the idea of his rocket becoming the satellite of the earth had presented itself, and he had immediately incorporated it into his scheme. The professor had figured out the amount of radium necessary to carry the rocket far enough away from the earth so that it would not turn around and crash, and still be not so far away but what the earth's gravitational attraction would keep it from leaving the vicinity of the earth and the solar system. Like the moon, it would forever revolve around the earth.

He had chosen an orbit sixty-five thousand miles from the earth for his rocket to follow. The only fears he had entertained concerned the huge meteors which careened through space at tremendous rates of speed. He had overcome this obstacle, however, and had eliminated the possibilities of a collision with these stellar juggernauts. In the rocket were installed radium repulsion rays which swerved all approaching meteors from the path of the rocket as they entered the vicinity of the space wanderer.

The aged professor had prepared for every contingency, and had set down to rest from his labors, reveling in the stupendous, unparalleled results he would obtain. Never would his body undergo decay; and never would his bones bleach to return to the dust of the earth from which all men originally came and to which they must return. His body would remain millions of years in a perfectly preserved state, untouched by the hoary palm of such time as only geologists and astronomers can conceive.

His efforts would surpass even the wildest dreams of H. Rider Haggard, who depicted the wondrous, embalming practices of the ancient nation of Kor in his immortal novel, "She," wherein Holly, under the escort of the incomparable Ayesha, looked upon the magnificent, lifelike masterpieces of embalming by the long-gone peoples of Kor.

With the able assistance of a nephew, who carried out his instructions and wishes following his death, Professor Jameson was sent upon his pilgrimage into space within the rocket he himself had built. The nephew and heir kept the secret forever locked in his heart.

Generation after generation had passed upon its way. Gradually humanity had come to die out, finally disappearing from the earth altogether. Mankind was later replaced by various other forms of life which dominated the globe for their allotted spaces of time before they too became extinct. The years piled up on one another, running into millions, and still the Jameson Satellite kept its lonely vigil around the earth, gradually closing the distance between satellite and planet, yielding reluctantly to the latter's powerful attraction.

Forty million years later, its orbit ranged some twenty thousand miles from the earth while the dead world edged ever nearer the cooling sun whose dull, red ball covered a large expanse of the sky. Surrounding the flaming sphere, many of the stars could be perceived through the earth's thin, rarefied atmosphere. As the earth cut in slowly and gradually toward the solar luminary, so was the moon revolving ever nearer the earth, appearing like a great gem glowing in the twilight sky.

The rocket containing the remains of Professor Jameson continued its endless travel around the great ball of the earth whose rotation had now ceased entirely—one side forever facing the dying sun. There it pursued its lonely way, a cosmic coffin, accompanied by its funeral cortege of scintillating stars amid the deep silence of the eternal space which enshrouded it. Solitary it remained, except for the occasional passing of a meteor flitting by at a remarkable speed on its aimless journey through the vacuum between the far-flung worlds.

Would the satellite follow its orbit to the world's end, or would its supply of radium soon exhaust itself after so many eons of time, converting the rocket into the prey of the first large meteor which chanced that way? Would it some day return to the earth as its nearer approach portended, and increase its acceleration in a long arc to crash upon the surface of the dead planet? And when the rocket terminated its career, would the body of Professor Jameson be found perfectly preserved or merely a crumbled mound of dust?

CHAPTER I

40,000,000 Years After

Entering within the boundaries of the solar system, a long, dark, pointed craft sped across the realms of space towards the tiny point of light which marked the dull red ball of the dying sun which would some day lie cold and dark forever. Like a huge meteor it flashed into the solar system from another chain of planets far out in the illimitable Universe of stars and worlds, heading towards the great red sun at an inconceivable speed.

Within the interior of the space traveler, queer creatures of metal labored at the controls of the space flyer which juggernauted on its way towards the far-off solar luminary. Rapidly it crossed the orbits of Neptune and Uranus and headed sunward. The bodies of these queer creatures were square blocks of a metal closely resembling steel, while for appendages, the metal cube was upheld by four jointed legs capable of movement. A set of six tentacles, all metal, like the rest of the body, curved outward from the upper half of the cubic body. Surmounting it was a queer-shaped head rising to a peak in the center and equipped with a circle of eyes all the way around the head. The creatures, with their mechanical eyes equipped with metal shutters, could see in all directions. A single eye pointed directly upward, being situated in the space of the peaked head, resting in a slight depression of the cranium.

These were the Zoromes of the planet Zor which rotated on its way around a star millions of light years distant from our solar system. The Zoromes, several hundred thousand years before, had reached a stage in science, where they searched for immortality and eternal relief from bodily ills and various deficiencies of flesh and blood anatomy. They had sought freedom from death, and had found it, but at the same time they had destroyed the propensities for birth. And for several hundred thousand years there had been no births and few deaths in the history of the Zoromes.

This strange race of people had built their own mechanical bodies, and by operation upon one another had removed their brains to the metal heads from which they directed the functions and movements of their inorganic anatomies. There had been no deaths due to worn-out bodies. When one part of the mechanical men wore out, it was replaced by a new part, and so the Zoromes continued living their immortal lives which saw few casualties. It was true that, since the innovation of the machines, there had been a few accidents which had seen the destruction of the metal heads with their brains. These were irreparable. Such cases had been few, however, and the population of Zor had decreased but little. The machine men of Zor had no use for atmosphere, and had it not been for the terrible coldness of space, could have just as well existed in the ether void as upon some planet. Their metal bodies, especially their metal-encased brains, did require a certain amount of heat even though they were able to exist comfortably in temperatures which would instantly have frozen to death a flesh-and-blood creature.

The most popular pastime among the machine men of Zor was the exploration of the Universe. This afforded them a never ending source of interest in the discovery of the variegated inhabitants and conditions of the various planets on which they came to rest. Hundreds of space ships were sent out in all directions, many of them being upon their expeditions for hundreds of years before they returned once more to the home planet of far-off Zor.

This particular space craft of the Zoromes had entered the solar system whose planets were gradually circling in closer to the dull red ball of the declining sun. Several of the machine men of the space craft's crew, which numbered some fifty individuals, were examining the various planets of this particular planetary system carefully through telescopes possessing immense power.

These machine men had no names and were indexed according to letters and numbers. They conversed by means of thought impulses, and were neither capable of making a sound vocally nor of hearing one uttered.

"Where shall we go?" queried one of the men at the controls questioning another who stood by his side examining a chart on the wall.

"They all appear to be dead worlds, 4R-3579," replied the one addressed, "but the second planet from the sun appears to have an atmosphere which might sustain a few living creatures, and the third planet may also prove interesting for it has a satellite. We shall examine the inner planets first of all, and explore the outer ones later if we decide it is worth the time."

"Too much trouble for nothing," ventured 9G-721. "This system of planets offers us little but what we have seen many times before in our travels. The sun is so cooled that it cannot sustain the more common life on its planets, the type of life forms we usually find in our travels. We should have visited a planetary system with a brighter sun."

"You speak of common life," remarked 25X-987. "What of the uncommon life? Have we not found life existent on cold, dead planets with no sunlight and atmosphere at all?"

"Yes, we have," admitted 9G-721, "but such occasions are exceedingly rare."

"The possibility exists, however, even in this case," reminded 4R-3579, "and what if we do spend a bit of unprofitable time in this one planetary system—haven't we all an endless lifetime before us? Eternity is ours."

"We shall visit the second planet first of all," directed 25X-987, who was in charge of this particular expedition of the Zoromes, "and on the way there we shall cruise along near the third planet to see what we can of the surface. We may be able to tell whether or not it holds anything of interest to us. If it does, after visiting the second planet, we shall then return to the third. The first world is not worth bothering with."

The space ship from Zor raced on in a direction which would take it several thousand miles above the earth and then on to the planet which we know as Venus. As the space ship rapidly neared the earth, it slackened its speed, so that the Zoromes might examine it closely with their glasses as the ship passed the third planet.

Suddenly, one of the machine men ran excitedly into the room where 25X-987 stood watching the topography of the world beneath him.

"We have found something!" he exclaimed.

"What?"

"Another space ship!"

"Where?"

"But a short distance ahead of us on our course. Come into the foreport of the ship and you can pick it up with the glass."

"Which is the way it's going?" asked 25X-987.

"It is behaving queerly," replied the machine man of Zor. "It appears to be in the act of circling the planet."

"Do you suppose that there really is life on that dead world—intelligent beings like ourselves, and that this is one of their space craft?"

"Perhaps it is another exploration craft like our own from some other world," was the suggestion.

"But not of ours," said 25X-987.

Together, the two Zoromes now hastened into the observation room of the space ship where more of the machine men were excitedly examining the mysterious space craft, their thought impulses flying thick and fast like bodiless bullets.

"It is very small!"

"Its speed is slow!"

"The craft can hold but few men," observed one.

"We do not yet know of what size the creatures are," reminded another. "Perhaps there are thousands of them in that space craft out there. They may be of such a small size that it will be necessary to look twice before finding one of them. Such beings are not unknown."

"We shall soon overtake it and see."

"I wonder if they have seen us?"

"Where do you suppose it came from?"

"From the world beneath us," was the suggestion.

"Perhaps."

CHAPTER II

The Mysterious Space Craft

The machine men made way for their leader, 25X-987, who regarded the space craft ahead of them critically.

"Have you tried communicating with it yet?" he asked.

"There is no reply to any of our signals," came the answer.

"Come alongside of it then," ordered their commander. "It is small enough to be brought inside our carrying compartment, and we can see with our penetration rays just what manner of creatures it holds. They are intelligent, that is certain, for their space ship does imply as much."

The space flyer of the Zoromes slowed up as it approached the mysterious wanderer of the cosmic void which hovered in the vicinity of the dying world.

"What a queer shape it has," remarked 25X-987. "It is even smaller than I had previously calculated."

A rare occurrence had taken place among the machine men of Zor. They were overcome by a great curiosity which they could not allow to remain unsatiated. Accustomed as they were to witnessing strange sights and still stranger creatures, meeting up with weird adventures in various corners of the Universe, they had now become hardened to the usual run of experiences which they were in the habit of encountering. It took a great deal to arouse their unperturbed attitudes. Something new, however, about this queer space craft had gripped their imaginations, and perhaps a subconscious influence asserted to their minds that here they have come across an adventure radically unusual.

"Come alongside it," repeated 25X-987 to the operator as he returned to the control room and gazed through the side of the space ship in the direction of the smaller cosmic wanderer.

"I'm trying to," replied the machine man, "but it seems to jump away a bit every time I get within a certain distance of it. Our ship seems to jump backward a bit too."

"Are they trying to elude us?"

"I don't know. They should pick up more speed if that is their object."

"Perhaps they are now progressing at their maximum speed and cannot increase their acceleration any more."

"Look!" exclaimed the operator. "Did you just see that? The thing has jumped away from us again!"

"Our ship moved also," said 25X-987. "I saw a flash of light shoot from the side of the other craft as it jumped."

Another machine man now entered and spoke to the commander of the Zorome expedition.

"They are using radium repellent rays to keep us from approaching," he informed.

"Counteract it," instructed 25X-987.

The man left, and now the machine man at the controls of the craft tried again to close with the mysterious wanderer of the space between planets. The effort was successful, and this time there was no glow of repulsion rays from the side of the long metal cylinder.

They now entered the compartment where various objects were transferred from out the depths of space to the interplanetary craft. Then patiently they waited for the rest of the machine men to open the side of their space ship and bring in the queer, elongated cylinder.

"Put it under the penetration ray!" ordered 25X-987. "Then we shall see what it contains!"

The entire group of Zoromes were assembled about the long cylinder, whose low nickel-plated sides shone brilliantly. With interest they regarded the fifteen-foot object which tapered a bit towards its base. The nose was pointed like a bullet. Eight cylindrical protuberances were affixed to the base while the four sides were equipped with fins such as are seen on aerial bombs to guide them in a direct, unswerving line through the atmosphere. At the base of the strange craft there projected a lever, while in one side was a door which, apparently opened outward. One of the machine men reached forward to open it but was halted by the admonition of the commander.

"Do not open it up yet!" he warned. "We are not aware of what it contains!"

Guided by the hand of one of the machine men, a series of lights shone down upon the cylinder. It became enveloped in a haze of light which rendered the metal sides of the mysterious space craft dim and indistinct while the interior of the cylinder was as clearly revealed as if there had been no covering. The machine men, expecting to see at least several, perhaps many, strange creatures moving about within the metal cylinder, stared aghast at the sight they beheld. There was but one creature, and he was lying perfectly still, either in a state of suspended animation or else of death. He was about twice the height of the mechanical men of Zor. For a long time they gazed at him in a silence of thought, and then their leader instructed them.

"Take him out of the container."

The penetration rays were turned off, and two of the machine men stepped eagerly forward and opened the door. One of them peered within at the recumbent body of the weird-looking individual with the four appendages. The creature lay up against a luxuriously upholstered interior, a strap affixed to his chin while four more straps held both the upper and lower appendages securely to the insides of the cylinder. The machine man released these, and with the help of his comrade removed the body of the creature from the cosmic coffin in which they had found it.

"He is dead!" pronounced one of the machine men after a long and careful examination of the corpse. "He has been like this for a long time."

"There are strange thought impressions left upon his mind," remarked another.

One of the machine men, whose metal body was of a different shade than that of his companions, stepped forward, his cubic body bent over that of the strange, cold creature who was garbed in fantastic accoutrements. He examined the dead organism a moment, and then he turned to his companions.

"Would you like to hear his story?" he asked.

"Yes!" came the concerted reply.

"You shall, then," was the ultimatum. "Bring him into my laboratory. I shall remove his brain and stimulate the cells into activity once more. We shall give him life again, transplanting his brain into the head of one of our machines."

With these words he directed two of the Zoromes to carry the corpse into the laboratory.

As the space ship cruised about in the vicinity of this third planet which 25X-987 had decided to visit on finding the metal cylinder with its queer inhabitant, 8B-52, the experimenter, worked unceasingly in his laboratory to revive the long-dead brain cells to action once more. Finally, after consummating his desires and having his efforts crowned with success, he placed the brain within the head of a machine. The brain was brought to consciousness. The creature's body was discarded after the all-important brain had been removed.

CHAPTER III

Recalled to Life

As Professor Jameson came to, he became aware of a strange feeling. He was sick. The doctors had not expected him to live; they had frankly told him so—but he had cared little in view of the long, happy years stretched out behind him. Perhaps he was not to die yet. He wondered how long he had slept. How strange he felt—as if he had no body. Why couldn't he open his eyes? He tried very hard. A mist swam before him. His eyes had been open all the time but he had not seen before. That was queer, he ruminated. All was silent about his bedside. Had all the doctors and nurses left him to sleep—or to die?

Devil take that mist which now swam before him, obscuring everything in line of vision. He would call his nephew. Vainly he attempted to shout the word "Douglas," but to no avail. Where was his mouth? It seemed as if he had none. Was it all delirium? The strange silence—perhaps he had lost his sense of hearing along with his ability to speak—and he could see nothing distinctly. The mist had transferred itself into a confused jumble of indistinct objects, some of which moved about before him.

He was now conscious of some impulse in his mind which kept questioning him as to how he felt. He was conscious of other strange ideas which seemed to be impressed upon his brain, but this one thought concerning his indisposition clamored insistently over the lesser ideas. It even seemed just as if someone was addressing him, and impulsively he attempted to utter a sound and tell them how queer he felt. It seemed as if speech had been taken from him. He could not talk, no matter how hard he tried. It was no use. Strange to say, however, the impulse within his mind appeared to be satisfied with the effort, and it now put another question to him. Where was he from? What a strange question—when he was at home. He told them as much. Had he always lived there? Why, yes, of course.

The aged professor was now becoming more astute as to his condition. At first it was only a mild, passive wonderment at his helplessness and the strange thoughts which raced through his mind. Now he attempted to arouse himself from the lethargy.

Quite suddenly his sight cleared, and what a surprise! He could see all the way around him without moving his head! And he could look at the ceiling of his room! His room? Was it his room! No— It just couldn't be. Where was he? What were those queer machines before him? They moved on four legs. Six tentacles curled outward from their cubical bodies. One of the machines stood close before him. A tentacle shot out from the object and rubbed his head. How strange it felt upon his brow. Instinctively he obeyed the impulse to shove the contraption of metal from him with his hands.

His arms did not rise, instead six tentacles projected upward to force back the machine. Professor Jameson gasped mentally in surprise as he gazed at the result of his urge to push the strange, unearthly looking machine-caricature from him. With trepidation he looked down at his own body to see where the tentacles had come from, and his surprise turned to sheer fright and amazement. His body was like the moving machine which stood before him! Where was he? What ever had happened to him so suddenly? Only a few moments ago he had been in his bed, with the doctors and his nephew bending over him, expecting him to die. The last words he had remembered hearing was the cryptic announcement of one of the doctors.

"He is going now."

But he hadn't died after all, apparently. A horrible thought struck him! Was this the life after death? Or was it an illusion of the mind? He became aware that the machine in front of him was attempting to communicate something to him. How could it, thought the professor, when he had no mouth. The desire to communicate an idea to him became more insistent. The suggestion of the machine man's question was in his mind. Telepathy, thought he.

The creature was asking about the place whence he had come. He didn't know; his mind was in such a turmoil of thoughts and conflicting ideas. He allowed himself to be led to a window where the machine with waving tentacle pointed towards an object outside. It was a queer sensation to be walking on the four metal legs. He looked from the window and he saw that which caused him to nearly drop over, so astounded was he.

The professor found himself gazing out from the boundless depths of space across the cosmic void to where a huge planet lay quiet. Now he was sure it was an illusion which made his mind and sight behave so queerly. He was troubled by a very strange dream. Carefully he examined the topography of the gigantic globe which rested off in the distance. At the same time he could see back of him the concourse of mechanical creatures crowding up behind him, and he was aware of a telepathic conversation which was being carried on behind him—or just before him. Which was it now? Eyes extended all the way around his head, while there existed no difference on any of the four sides of his cubed body. His mechanical legs were capable of moving in any of four given directions with perfect ease, he discovered.

The planet was not the earth—of that he was sure. None of the familiar continents lay before his eyes. And then he saw the great dull red ball of the dying sun. That was not the sun of his earth. It had been a great deal more brilliant.

"Did you come from that planet?" came the thought impulse from the mechanism by his side.

"No," he returned.

He then allowed the machine men—for he assumed that they were machine men, and he reasoned that, somehow or other they had by some marvelous transformation made him over just as they were—to lead him through the craft of which he now took notice for the first time. It was an interplanetary flyer, or space ship, he firmly believed.

25X-987 now took him to the compartment which they had removed him to from the strange container they had found wandering in the vicinity of the nearby world. There they showed him the long cylinder.

"It's my rocket satellite!" exclaimed Professor Jameson to himself, though in reality every one of the machine men received his thoughts plainly. "What is it doing here?"

"We found your dead body within it," answered 25X-987. "Your brain was removed to the machine after having been stimulated into activity once more. Your carcass was thrown away."

Professor Jameson just stood dumfounded by the words of the machine man.

"So I did die!" exclaimed the professor. "And my body was placed within the rocket to remain in everlasting preservation until the end of all earthly time! Success! I have now attained unrivaled success!"

He then turned to the machine man.

"How long have I been that way?" he asked excitedly.

"How should we know?" replied the Zorome. "We picked up your rocket only a short time ago, which, according to your computation, would be less than a day. This is our first visit to your planetary system and we chanced upon your rocket. So it is a satellite? We didn't watch it long enough to discover whether or not it was a satellite. At first we thought it to be another traveling space craft, but when it refused to answer our signals we investigated."

"And so that was the earth at which I looked," mused the professor. "No wonder I didn't recognize it. The topography has changed so much. How different the sun appears—it must have been over a million years ago when I died!"

"Many millions," corrected 25X-987. "Suns of such size as this one do not cool in so short a time as you suggest."

Professor Jameson, in spite of all his amazing computations before his death, was staggered by the reality.

"Who are you?" he suddenly asked.

"We are the Zoromes from Zor, a planet of a sun far across the Universe."

25X-987 then went on to tell Professor Jameson something about how the Zoromes had attained their high stage of development and had instantly put a stop to all birth, evolution and death of their people, by becoming machine men.

CHAPTER IV

The Dying World

"And now tell us of yourself," said 25X-987, "and about your world."

Professor Jameson, noted in college as a lecturer of no mean ability and perfectly capable of relating intelligently to them the story of the earth's history, evolution and march of events following the birth of civilization up until the time when he died, began his story. The mental speech hampered him for a time, but he soon became accustomed to it so as to use it easily, and he found it preferable to vocal speech after a while. The Zoromes listened interestedly to the long account until Professor Jameson had finished.

"My nephew," concluded the professor, "evidently obeyed my instructions and placed my body in the rocket I had built, shooting it out into space where I became the satellite of the earth for these many millions of years."

"Do you really want to know how long you were dead before we found you?" asked 25X-987. "It would be interesting to find out."

"Yes, I should like very much to know," replied the professor.

"Our greatest mathematician, 459C-79, will tell it to you." The mathematician stepped forward. Upon one side of his cube were many buttons arranged in long columns and squares.

"What is your unit of measuring?" he asked.

"A mile."

"How many times more is a mile than is the length of your rocket satellite?"

"My rocket is fifteen feet long. A mile is five thousand two hundred and eighty feet."

The mathematician depressed a few buttons.

"How far, or how many miles from the sun was your planet at that time?"

"Ninety-three million miles," was the reply.

"And your world's satellite—which you call moon from your planet—earth?"

"Two hundred and forty thousand miles."

"And your rocket?"

"I figured it to go about sixty-five thousand miles from the earth."

"It was only twenty thousand miles from the earth when we picked it up," said the mathematician, depressing a few more buttons. "The moon and sun are also much nearer your planet now."

Professor Jameson gave way to a mental ejaculation of amazement.

"Do you know how long you have cruised around the planet in your own satellite?" said the mathematician. "Since you began that journey, the planet which you call the earth has revolved around the sun over forty million times."

"Forty—million—years!" exclaimed Professor Jameson haltingly. "Humanity must then have all perished from the earth long ago! I'm the last man on earth!"

"It is a dead world now," interjected 25X-987.